Mayme Kratz

by Richard Nilsen

When I was young, I don’t know how many times I visited the Hayden Planetarium in New York. As a boy and as a teenager, the planetarium and its adjacent American Museum of Natural History were anchors to my sense of the world. It wasn’t just the science I learned there (I quickly figured out that science required more math than I was willing to chew on); in fact, it was really the esthetics. I thought the photographs I saw of the stars and galaxies at the planetarium (and the bones and dioramas I saw at the museum) were the most beautiful things I knew. They gave me a nascent awareness of the sublime — a sense of the vastness and intensity of the universe and the tiny corner I inhabited. An affirmation that the sum of creation was not limited to the suburban banality I knew in northern New Jersey. That came as such a relief.

Those astrophotographs were the birth of an esthetic sense that has never left me.

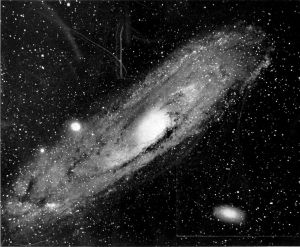

Long before the technicolor glories from the Hubble telescope, it was the now-primitive black-and-white photos from the Mount Wilson and Lick observatories that moved me. At the planetarium, they were glass transparencies lit from behind in a darkened corridor and it was the visual contrast between the texture of bright specks against an unfathomable black background that excited me. I have searched long for a book that would have those photographs in it, printed with a velvety black ink, to reignite that sense of wonder, but I’m afraid that like much in the childhood of any of us, such pleasures are unrecoverable.

Yet, I found something like that sense again in Phoenix, when, as the art critic for The Arizona Republic I followed the career of Mayme Kratz. One of the very first shows I reviewed for the paper, in 1987, was Kratz’s ”Vertigo Series” show at the Scottsdale Center for the Arts, which was mostly paintings of falling or floating women. Between then and now, Kratz has grown considerably. Her art currently has more dimensions and, what is more, is better crafted.

One of the things I railed against on my journalistic soapbox was the proliferation of academic and didactic artists flailing away with titrations of French philosophy and installations espousing ideological points better made in political cartoons — such art giving us recipes instead of food, menus instead of meals. I longed for art that spoke to us about the experience of being alive, art that awoke me to the pleasures and pains of the existence I knew. Art not about art, but about life.

Yet, to be successful as art, it needed to be more than pictures of pretty things, it needed to be abstracted to some degree, to be made metaphorical rather than literal, to have resonance, like the plummy sounds of a chorus of French horns. It couldn’t hit me over the head with a message, but rather elicit from my inner core something buried there — something I recognized when seeing the art. That harmonization of the inner as a mirror of the outer brings the viewer pleasure — even pleasure in the recognition of sorrow and loss, the pleasure in recognition of something shared, something profoundly human. This is what gives me so much utter pleasure in the works of Kratz.

The analogy with the photographs of spiral galaxies is hardly arbitrary. What attracted me to the photographs was the contrast between texture and flatness — stars in the blackness. Both necessary. In the large Kratz wallhangings, there is the same: some textured bit of nature embedded in industrially smooth colored translucent resin. You can see in many of them, the buried seeds or shells have been sanded smooth to the surface of the resin and often as a result slicing the seed or shell in half, opening their innards to view, and thereby giving them a rough and spiny texture that contrasts with the polish of the resin.

There is also the organic nature of the embedded morsels versus the manufactured sheen of the framing acrylic. This balance of oppositions gives them an ambiguous subtlety. One feels the sensuous darts of the natural bits and the bland soothingness of the color that engulfs them.

I have enjoyed the art of Mayme Kratz for decades now, and it is one of my regrets that, having moved away from Arizona, I no longer see her shows in person. Seeing them digitally online cannot suffice — the computer screen (or printed page) cannot convey the deep color, the physicality of the texture, or the scale — and it is their palpable presence that carries the resonance (I almost wrote “resin-ance.”) But I carry with me the remembrance of them, just as I do the glowing pictures of distant galaxies. They illuminate my life.

I have written about her work many times over the years, but I wanted to include the close of a review I wrote in 1998 for a show the artist had at the Lisa Sette Gallery, when it was still in Scottsdale:

“For most of these pieces are constructed out of the findings Kratz accumulates while walking. There are butterfly wings, moths, sunflowers, a wizened lizard and bee wings, in addition to an entire dead bird, the capstone to her 5-foot-tall mini-obelisk calledThis Bird. The piece captures the light and glows with life. The bird itself, half obscured in the foggy thickness of an amberlike resin, is spread-winged in imitation of flight, yet obviously no longer alive. The ambiguity is central to Kratz’s art.

“The work is always ravishingly gorgeous, but it is never about that. If anything, it is about death and loss, the passing of seasons and years, the process of living and dying. It all seems as fragile as the nests, as stinging as the thorns on the ocotillo.

“The dead bird is only one example. Other titles tell the tale: Late Summer, Winter of Listening, Lost and Found, Ending August,What Remains. There is a deep nostalgia in the work that is not cheap sentiment, but profound emotion.

“In Out of Silence, the glistening cicada wings, like veins of silver, float in the darkness of the resin, and are seen, dimly, inside the work and not on its surface. You are forced to consider what is not obvious.

“Always, there is the sense of looking through the work, rather than at it, like kelp seen floating under the sea surface.

“ ‘What I deal with is a battle between dark and light, between what’s seen and what’s unseen,’ she once told me.

“It is work that is ambiguous without being obscure, subtle without being feeble, raw without being unfinished, emotional without being overwrought.

“And, most of all, it is beautiful without being pretty.”

Richard Nilsen inspired many ideas and memories at the salons he presented through the years when he was an arts critic and movie, travel, and features writer at The Arizona Republic. A few years ago, Richard and his wife moved to North Carolina. We want to continue our connection with Richard and have asked him to be a regular contributor to the Spirit of the Senses Journal. We asked Richard to write short essays that were inspired by the salons.

.

Pretty meaty to read. The man can write. Is there going to be a book?

He’s right on about the astrophotographs.

Art >