Eye on Picasso

.

by Richard Nilsen

.

Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz y Picasso was a very impatient man, perhaps because his name takes so long to say or write.

.

I say he was impatient on the evidence of his paintings. I certainly never met the man. But I have seen a boatload of his paintings in person and hundreds in reproduction, and they all tell me he didn’t have the patience to spend time on their finishing touches.

.

Don’t misunderstand: Pablo Picasso was a great artist, and for many reasons. But he was not what I would call a great painter. Let’s take a look.

.

There was a time when many thought that Picasso’s art was a hoax. You know, the “My kid could paint better than that,” and serious-minded critics would say, “First, you have to be able to master the techniques before you can experiment with abstraction.” (Yeah, this was a while ago).

.

But then, some of the young Picasso’s art, from his adolescence, began showing up and it was clear that he had been a masterful draftsman and could draw and paint as realistically as anyone.

.

He could pump out an academic figure study like an Old Master. And he could put on canvas as realistic a painting as you could wish. Just look at some of these, from 1893, when the artist was 12, and 1896. It is clear he could do anything. But he didn’t: By the turn of the century, he had been taken with more modern trends in art, from Impressionism to Post-Impressionism, to Fauvism and Expressionism. His style loosened and the works became sketchier.

.

This evolution of style was characteristic not only of Picasso, but of other artists, writers and poets. There had been Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Cezanne — all with different styles.

.

By the middle of the last century (that’s the 20th, remember), Modernism had not only established itself, but become entrenched. Its hagiography had been codified and the heads of its various branches were Igor Stravinsky in music, James Joyce in prose, Ezra Pound in verse, and Picasso on canvas.

.

These were hardly the only names in the mix, and they may not even have been the best artists working, but they became the names we all knew. They are the names in the anthologies and textbooks.

.

And they all burned through styles. Stravinsky went from late Romantic chromaticism, to a savage primitivism, to Neo-Classicism and finally to his version of 12-tone serialism. Joyce from some of the most beautiful, clear prose in The Dubliners to the stream-of-conscious jumble in Ulysses and into the paronomastic almost-abstract gibberish of Finnegans Wake. Pound began with highly poeticized Edwardian prettiness to a hard-edged sarcasm and into his own form of pan-linguistic word salad.

.

Most serious artists go through stylistic growth from early to late periods, but Modernism seems less like organic growth and more like a conscious seeking-out of something new, something that would get attention. Pound’s battle cry was, “Make it new!” Where style had been a function of personality, it became a “brand” and ever newer versions were sought, like updating your car every few years.

.

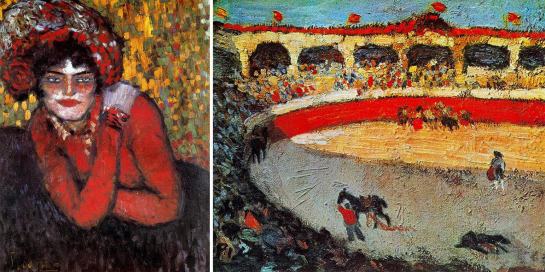

I’m being too harsh here, but to make a point. Picasso kept evolving, from that early Expressionism

.

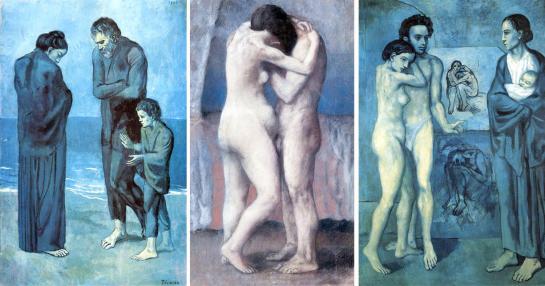

To the famous “Blue Period

.

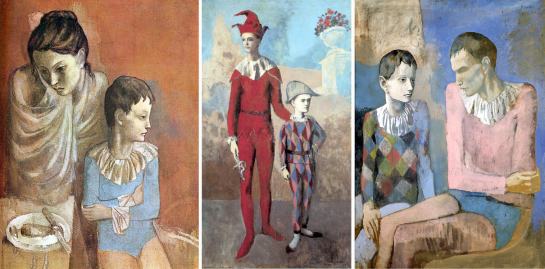

Through a subsequent “Rose Period”

.

to African primitivism,

.

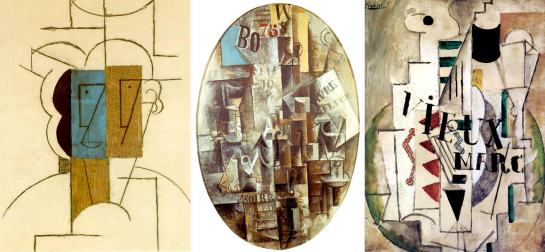

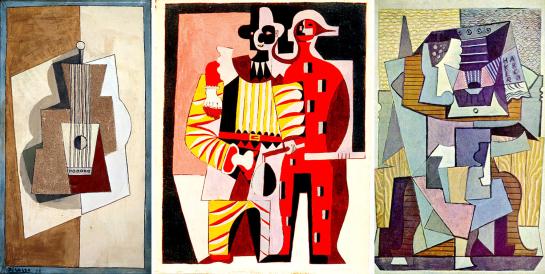

to analytic Cubism,

.

to Synthetic Cubism,

.

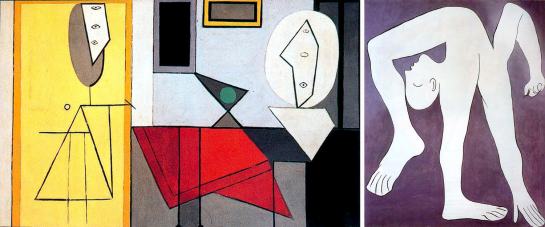

to Surrealism

.

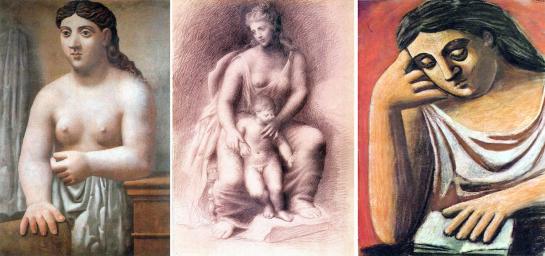

and Neo-Classicism

.

Then a brief period in the mid 1920s of what might look like a return to a kind of realism

.

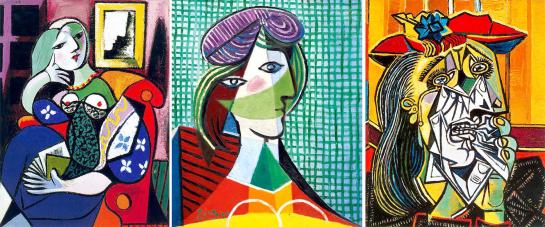

and then, into what can only be termed Picasso-ism — his playful mix of everything and anything, usually turned out in a few hours and often rather haphazard.

.

And this gets to my main point: That Picasso was an epically inventive visual artist, clever in the first degree. But from his earliest work onward, was always rather indifferent about the craft of painting. His application of paint to canvas was often sloppy; parts of many paintings were essentially unfinished; many are more caricature than character; even his color choice often seems unconsidered — any red might do, any green, any blue. His art is one of suggestion rather than observation.

.

This was typical of his approach in other ways. Where most artists use their work to react to life and the world, Picasso seemed always more interested in cultural tropes. That is, he picked on several archetypes — or stereotypes — and re-imagined them over and over. These are themes straight from his brain, without recourse to the actual world.

.

There were bulls and bullfights; Harlequin and Pulcinello; circus performers; the down-and-out; birds; women, both as portrait and as nude; satyrs, fauns and demons; still lifes; and over and over: the artist and his model.

.

He drew these subjects from his mind, not his eye. And the goal seems to have been to get them down as fast as possible and to get on to the next canvas. During the Renaissance, an artist might work on a painting for a month, polishing it to a perfect finish; Picasso seems to have been more likely to complete several paintings in a day.

.

You can see how fast he works (and how fast his mind could work) in the 1956 film by director Henri-Georges Clouzot, The Mystery of Picasso, in which, over the course of its 75 minutes, the shirtless Picasso completes 20 drawings and paintings. Of course, most of these are merely sketches, but you can see how fast his brain is functioning — and how diagrammatic his take on the visual world really is. He is not capturing the way the world looks, but rather creating hieroglyphs to be read, the way his dove is a symbol for “peace.” Or the stick-figure man or woman on restroom doors.

.

The one time he made the effort, worked over many preliminary sketches and worked his canvas to a fine finish, he produced what is probably the most important, most powerful painting of the century — his 1937 Guernica, about the bombing of the Basque city by Nazi planes supporting the Fascist forces of Francisco Franco. The giant painting —roughly 12 feet by 25 feet — hung for many years at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, as, under the will of the artist, it could not be returned to Spain until the reestablishment of democracy. It finally went home to Madrid in 1981.

.

I saw the painting many times when I was a young man, living just outside New York, and visiting MoMA as often as I could. It anchored one end of the museum and you could see it as soon as you got out of the elevator on the second floor, the focus of the whole museum.

.

I’m not saying that we would have been better off if Picasso had spent more time on fewer paintings — his prodigious energy is largely why we honor him. But what can’t be ignored is that his work is often slapdash, sometimes not much more than a doodle.

.

When I was young, and for the first three-quarters of the 20th Century, Picasso was a colossus, almost universally acclaimed as the era’s greatest artist — the Muhammad Ali of the paintbrush — but in recent years, his primacy has receded. Partly because the adrenalin rush of Modernism has petered out; partly because the art market has become so much more simply part of the financial world, more interested in investment and less in the actual art; and perhaps most of all because Picasso, the man, has been revealed as such a misogynist pig. He was a very unpleasant man.

.

Since the publication of the four-volume biography by John Richardson, it has been clear what a self-serving, self-promoting, egotist he was. He went through wives and mistresses, using them and often abusing them. Once we thought of him as the great stud of art, now more like a frat boy with little care for the women in his life. Fernande Olivier, Olga Khokhlova, Marie-Thérèse Walter, Dora Maar, Françoise Gilot, Jacqueline Roque — there and gone.

.

Then, there was the semi-criminal past, selling fraudulent or stolen art, and footsying with the Nazis in occupied wartime France. In our current more censorious age, we more likely to knock the laurels off the heads of our writers, artists, filmmakers and actors — Did they diddle underage girls? Did they coddle to dictators? Did they steal the credit due to women? Were their intentions less than pure?

.

If we give in to these worries, we will have to strike from the record much of our cultural heritage. Artists are just as human as the rest of us.

.

And so, I forgive the genius his sins — they are past and he is dead — and honor the art. But I cannot ever not notice that for all his brilliance, Picasso was an indifferent craftsman. When I look at his work, I see the careless brushwork, the muddy colors, the repetitive subject matter.

.

My own youthful enthusiasm for Picasso has aged into a mature appreciation for his accomplishments. However diminished he is in the public eye, he is still the dominant artistic name from the first half of the 20th century.

.

Richard Nilsen inspired many ideas and memories at the salons he presented through the years when he was an arts critic and movie, travel, and features writer at The Arizona Republic. A few years ago, Richard moved to North Carolina. We want to continue our connection with Richard and have asked him to be a regular contributor to the Spirit of the Senses Journal. We asked Richard to write short essays that were inspired by the salons.