.

.

“Hey, Mack! You want a piece of me!”

.

The fastest way to get a punch in the nose is to reply: “My name ain’t Mack.” At least in New York. In the American South, I believe, you would more likely be addressed as “Sir.” As in, “Sir, are you casting aspersions upon my family’s name?”

.

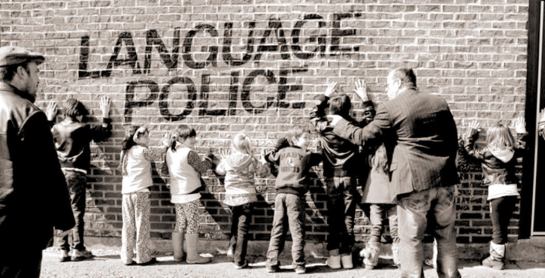

At issue is how you address someone whose name you don’t know, or a group of people in aggregate. Some anonymous word or phrase that conveys what you need to, without needing to use particulars. I call them “anonynyms” (yes, I’m making up a word for it).

.

Such a class of words or names is obviously needed, for interactions with groups, or for talking with strangers — or simply to create an insult.

.

I started thinking about this issue after being hit, again, with the most famous Southern expression, “You all,” or more properly, “Y’all.”

.

There was a time when the expression was said to be used only for groups of people, never when addressing a single person. But we all know that’s not true. I’ve heard many times the phrase used when talking to just one person. “Y’all going to the dance on Saturday?”

.

And so, to reestablish the plurality of the expression, many Southerners now use the doubled-term “all y’all.” “Is all y’all going to the dance?”

.

But where I grew up, in New Jersey, the substitute expression for a group of people being addressed is “youse guys.” “Is youse guys gonna be armed?” Notice the subtle use of the singular verb to-be with the plural expression.

.

It has been pointed out that in parts of the Midwest, particularly around Pittsburgh, the parallel expression is “y’ins.” As in, “Are y’ins going to the church supper?”

.

This is akin to another language habit that is not so often remarked, which is the expression used for addressing someone you don’t know, usually with the intent of venting some anger or vexation, although sometimes the expression is either more neutral or even, at times, affectionate. So, I decided to compile a list. I’m sure my catalog is incomplete. Perhaps you can add to it for me.

.

A child will often address a grownup man as “Mister.” As in “Hey, Mister, you dropped your wallet.”

.

If it is a woman being addressed, the child will often say “ma’am.” Or at least in earlier years when courtesy and etiquette still held sway. “Ma’am, ma’am, you forgot your umbrella.”

.

In the UK, you will sometimes hear a woman addressed as “madam,” as in “Madam, I assume you will be pressing charges.”

.

An alternate version, spoken by a young person, could be “Miss.” “I don’t know who took the chalk, Miss.” Often a pupil to a teacher.

.

Now largely out of date, but culturally fixed by Jerry Lewis is, “Hey, lady.” It’s hard not to imagine it other than in Lewis’ glass-etching voice.

.

Of course, where I came from, there are a multiplicity of such terms, almost always with the subtext of expressing anger or frustration.

.

“Look, Mack, we don’t want no trouble here.”

.

Or, “Hey, Pal, whatcha got there, under your coat?”

.

Perhaps “I don’t like the tone of your voice, Buster.”

.

“Look, Buddy, I don’t know where you think you’re going in that get-up.” Sometimes just shortened to Bud.

.

“Listen, chum, if you know what’s good for you…”

.

“Hey, Champ, can you move this car?”

.

Others include “Tiger,” “Sunshine,” “Cuz,” as in “cousin,” “Stud,” “Slick,” “Ace.” All of them with a strong undercurrent of mockery.

.

Then, there’s Boss, which, like many of such terms contains a backwash of condescension. Yelling on the highway, “Hey, Boss, pick a lane!” You can hear the word in Paul Newman’s voice from Cool Hand Luke, speaking to one of the guards: “Need some water here, Boss.”

.

Joe Biden is famous for his “Jack.” “Listen here Jack, I’ll only say this once so listen up.”

.

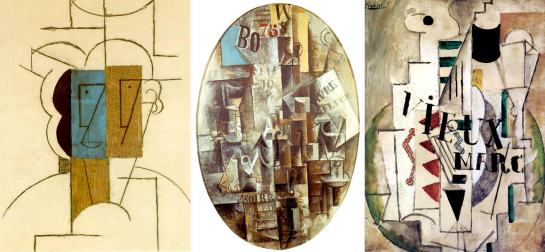

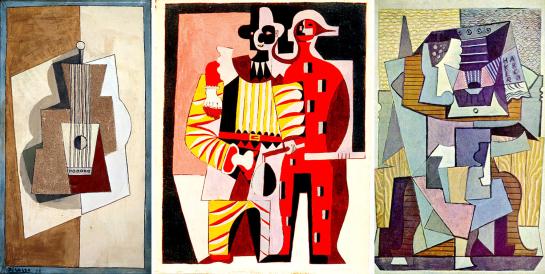

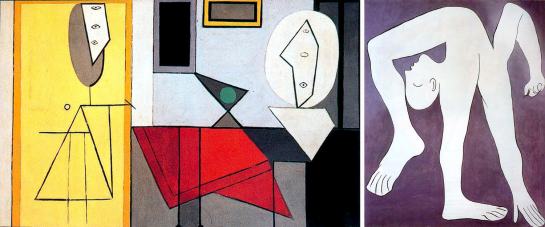

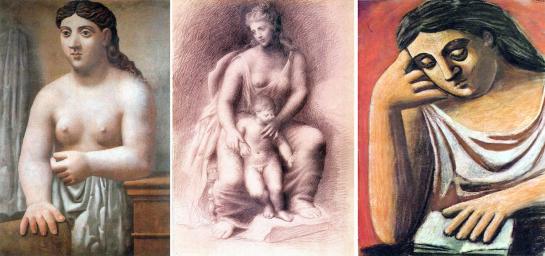

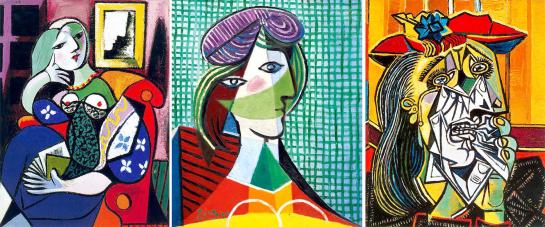

Sometimes, it is the name of an actual person that is spoken, as when you observe a person doing something stupid, like parking badly at a Walmart: “Hey, Einstein, try again.” Or the demotic critic: “Hey, Rembrandt, ya call that art?”

.

These are all almost exclusively used by men toward men. When addressing a woman, the version is “Sister.” “Any idea how fast you were driving, Sister?” Or, in James Cagney’s voice, “Sista.”

.

A good deal of this badinage comes from Yankeeland. The South has its own, but usually more genteel versions. You hear Sir a lot, and not always with the overtone of respect the work implies. It can be ironic. An older man, being avuncular, will address any male younger than himself as “Son.” “Son, let me give you the benefit of my years of experience.”

.

Though I was born a Yankee, I’ve lived in the South for the majority of my life, and I find that the implied politeness of “sir” has become my default. It is something you hear from Marines of impeccable posture, from distracted teens deferring to my annuated seniority, or from elderly Southern colonels implying an invitation to a duel.

.

The West gives us a few, like Pardner, as in “Smile when you say that, Pardner.” (The origin of the catchphrase comes from Owen Wister’s 1902 novel The Virginian, where it not only comes without the “pardner,” but turned front to back: “When you call me that, smile.”)

.

You can also hear Hoss and Chief. And Pilgrim is only coming out of John Wayne’s mouth, and I can only hear it in his voice.

.

Brother is used by African-Americans referring to Black men, when it is often pronounced as “bruva,” or shortened to “bro.” But it has its precedent in the Great Depression, devoid of race: “Brother, can you spare a dime?”

.

Broheem is used only for friends, and not for strangers, so it probably doesn’t count.

.

Women also have to address those unknown to them, but usually with a patina of affection, the way a waitress will say, “What’ll you have, Honey?” Or “I don’t know what you call, it, Sweetie, but where I come from…”

.

I want to mention the odd fact that in the American South, such anonynyms tend to be affectionate and often used for friends and family as well as for strangers, while, in the North, they are almost always aggressive.

.

I have no research to back this up, but I believe it stems from the fact that the South is traditionally agricultural and rural while the North tends to be urbanized. In rural areas, people tend to know everyone else, even across class and racial lines, and so they will either address someone with their actual name or a pet name. In the North, most people you meet will be strangers to you and a certain assertiveness in greeting is necessary to make sure you have carved yourself an adequate place in the society.

.

These anonynyms change over generations. In Jay Gatsby’s day, you might call someone “Sport.” In recent years, most of these anonynyms have distilled down to “Dude,” which increasingly is unisexual and used for both male and female by those under the age of 30. “Awesome, Dude!”

.

Historically, names get genericized as national sobriquets, like Mick or Paddy for the Irish or Fritz for the Germans. These are almost always insults, like calling a Mexican Pedro no matter what his actual name. Usually mispronounced as “Peedro.” And as such can be used as anonynyms when addressing a stranger whose ethnicity appears obvious. “Hey, Fritz, how ya like them apples.” This soon devolves into Archie Bunker territory. All Russians become “Ivan;” all Scandinavians become “Sven;” Italians are “Luigi;” and Frenchmen just become “Frenchie.”

.

But anonynyms occur in other cultures. In England, you can address a new acquaintance whose name you don’t know as “Old Sport.” A belittling name given to those you are scolding or arresting is “Sonny Jim,” as if it would be beneath you to learn such a scoundrel’s actual name. “Come along now, Sonny Jim.” The Irish have their own word for it: boyo.

.

In the UK, having pet names for strangers that you just drop into the end of sentences is a very working class thing and it makes the talker seem friendlier. The words used vary dramatically by region across the countries. Examples include “Flower,” “Treacle,” “Petal,” and a hundred more.

.

Northern England dialects have a wealth of such names, most commonly “Pet” and “Luv.” And while they are often meant endearingly, they can have a bit of an edge: “Don’t flatter yerself, luv.”

.

In Australia, the universal address is “Mate” or “Matey.” “You call that a knife, Mate?”

.

Finally, I must mention terms of endearment. Anyone who is married will know how silly it sounds to call your wife or husband by name. After 30 years of marriage, it is presumed you will each know what your spouse’s name is. And so, we fall into habitual terms of endearment. They become your mate’s default name. And like the real name, it is usual the same one each time. It is rare for a husband to call his wife different things. And so we get: Baby; Sweetie; Sweetie Pie, Sweetheart; Love; Sugar; Honey; Pet; Duckie. Well, that last one not so much.

.

In other cultures, there are equivalents, some just literal translations of the English terms, such as “Amour” in French. But there are some idiosyncratic ones as well. “Mon Chou,” in French, i.e. “My Cabbage.” “Maus” in German, “Mouse;” also “Hase,” or “Bunny.” German, of course, has all those portmanteau words, and so you get: Knuddelbärchen, “Cuddle Bear;” Honigkuchenpferd,” “Honey-Cake Horse;” and “Mausebär,” “Mouse-Bear.”

.

In Italy, you might talk to your “Fragolina,” or “Little Strawberry;” or your “Microbino Mio,” or “My Little Microbe.”

.

There are many more. And, except for that last one, they tend to fall into three categories: sugary foods; cute animals; and valuable objects, as in the German “Perle,” or “Pearl. The familiar German “Schatze,” or “Treasure.”

.

And there is a subset of this: Talking about your wife to your child or grandchildren. That’s why we have so many words for “grandmother” that become the names that grandchildren know them by. “Nana,” “Meemaw,” “Grammy,” “Bibi,” “Bubba,” “Yaya.” It just feels wrong to say to a five-year-old “Carole is going to the store to get ice cream,” when it’s really “Granny is going to the store.”

.

And so, at the end, we have to acknowledge that we all bear multiple names, for various social interactions. And this goes well beyond the nicknames we grew up with. What name does your spouse use to remind you to take out the garbage? What name does your grandchild use to ask you to bounce them on your knee? We are many names, many people, many roles to play.

.

.